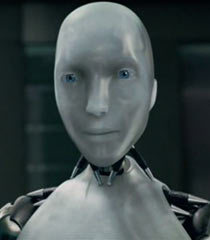

An obscure but telling sign of when the robots will have taken over will be in evidence when they’re allowed to be named as inventors on patent applications. But that day—when “I, Robot”-like artificial intelligence is thusly recognized as rivaling that of humans—hasn’t come about yet, at least not here in these United States. So Sonny – the good robot in the movie I, Robot” – cannot hold a patent, at least not yet!

That came as a disappointment to Stephen Thaler, creator of the DABUS (Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience) AI system, who had filed two patent applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office listing only DABUS as the inventor.

Thaler claimed he contributed nada to either invention and that DABUS should thus receive the patent, but his argument has failed to impress anyone from the USPTO on up to the Federal Circuit court that ruled on August 6 that the federal Patent Act requires that an application list a “natural person” as the inventor.

USPTO asserted in its initial response that “a machine does not qualify as an inventor” and did not budge when Thaler asked the office to reconsider. The Eastern District of Virginia turned down his appeal, stating that an inventor must be an “individual,” defined as a human being. (see: https://cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/21-2347.OPINION.8-5-2022_1988142.pdf for the full opinion.)

In reaffirming those rules, the Federal Circuit cited Section 100(f) of the Patent Act, which references “the individual … who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention,” and further relied on U.S. Supreme Court language (in a different statutory context) that interpreted “individual” as meaning “a human being, a person,” unless there is evidence Congress clearly intended it to be defined differently for purposes of a given law.

The Federal Circuit also referenced Section 115(b)(2) of the Patent act, which mandates that an inventor take an oath testifying that they “believe himself or herself to be the original inventor,” reasoning that such gendered pronouns could not apply to I, Robot and its ilk—and further noting that Thaler, not DABUS, submitted the application. In addition, the Federal Circuit noted precedent showing “that neither corporations nor sovereigns can be inventors” was rejected as not applying to the context of the case an argument Thaler put forth related to constitutional avoidance; it was rejected as “speculative and lack[ing] basis his policy-related argument” that awarding patents to AI would “encourage innovation and public disclosure.”

The decision pointedly did not rule out listing AI as a co-inventor along with humans, leaving open the possibility of patent protection for “inventions made by human beings with the assistance of AI.” So it’s possible that Asimov’s robot Sonny could get some credit in the future. The decision in Thaler v. Vidal also could lead to more inventorship challenges that seek discovery on whether AI was used in the invention process in such a way that it crossed the line from being simply a contributor, or tool, to serving as the actual inventor.

For now, though, those who want to list an AI as the sole inventor of a creation might want to try their luck in South Africa, which is the only country on the globe to allow AI to be named as inventors. Their legislature may be packed with fans of Isaac Asimovs “I, Robot.”

THIS POST CORRECTS AN EARLIER VERSION WHICH INCORRECTLY IDENTIFED THE NAME OF THE PLAINTIFF IN THE SUIT.

Chicago Business Attorney Blog

Chicago Business Attorney Blog